Don't Make Me Over

In between what we love, what we must do, and the ramifications of our decisions.

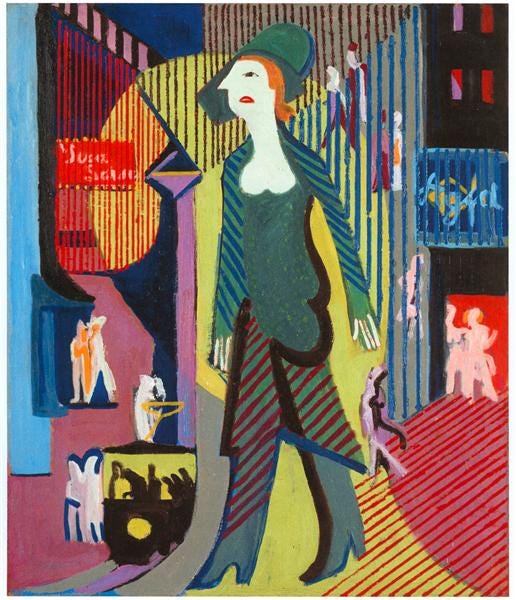

Unorthodox. The commitment to living two lives, bouncing between your identity on the dancefloor and the stagnating routine of workplace commitments. It’s a precarious path to follow, but one often chosen as the rewards of the normal don’t satisfy the internal need for experiences of resonance. Whether it’s escapism, connection, emotional release, or simply to exist for a fleeting moment, the continued choice to return to the dancefloor despite negative connotations will continue to prevail amongst a lot of us. To exist suspended between two realities, both with consequences and insistences that demand much from an individual, is exhausting, self-defeating and oftentimes idiotic. We travel through our twenties, gifted with an ability to continually revisit situations and experiences that bring us joy, lacking the weight of the bodily consequences that hold our attention in our thirties. It’s here that the combination of hangovers and comedowns is spliced with societal implied guilt that looks you square in the eye and asks, “Where do you see yourself in five years?” will send most committed weekenders running (usually to a marathon). But for many of us, that spark doesn’t wither. Sure, we may leave it unattended, try to stoke it with other briquettes or simply ignore it, but the fact of the matter is that when you do understand this about yourself, it at least allows some clarity and understanding. While the life of normality and comforts can have a list of critiques drawn up in a very short amount of time, it’s not uncommon to feel some sort of envy for this mode of existence. While they’re not living life on easy mode, they are very good at making it appear that way.

It’s often forgotten (and intentionally) the enormity of the demands we place upon ourselves to commit. The ability to actualise a commitment to expenditure, time, and exhaustion can be completed in a millisecond, thanks to the slightest enticement of possibility. Enormity may sound a tad dramatic to describe the act of going to dance at a club or festival. However, in the context of the present-day situation of our cost of living and infinite other uses of time, it holds some weight. Few activities exist with as many negative side effects that are easily committed to so often. Outside demands are cast aside simply and without a moment’s hesitation, easily traversing the thought web of “later” to “next week” to “maybe”. Sure, maybe you are one of these organised few that has achieved the serenity of balancing commitments. I raise my hat to you. For the vast majority caught in the cycle, the ability to decline is a skill yet to learn. Is this a positive way for your relationship with electronic music, drugs and nightlife culture to exist? Well, it’s an exciting one, it’s an infatuating one, it’s an intoxicating one. That’s the way we like to style it, as it feels fitting to the source material. Of course, contained within the ritual are emotional positives gained through our interaction with the space, music and movement. We can also attend simply because we want to go. Pinpointing the reason at the time can be a wasted venture. You do not need to be afflicted with the trials and tribulations of life to want to party. Our present-day over-analytical approach, created by overexposure to therapeutic language and our own attempts to solve a situation (guilty as charged), can often falter the simple need to enjoy. The drive reaches the surface and takes us on autopilot straight back to where we dance best. Nothing more, nothing less. With further inspection, depending on the individual’s circumstances, we can uncover bigger answers.

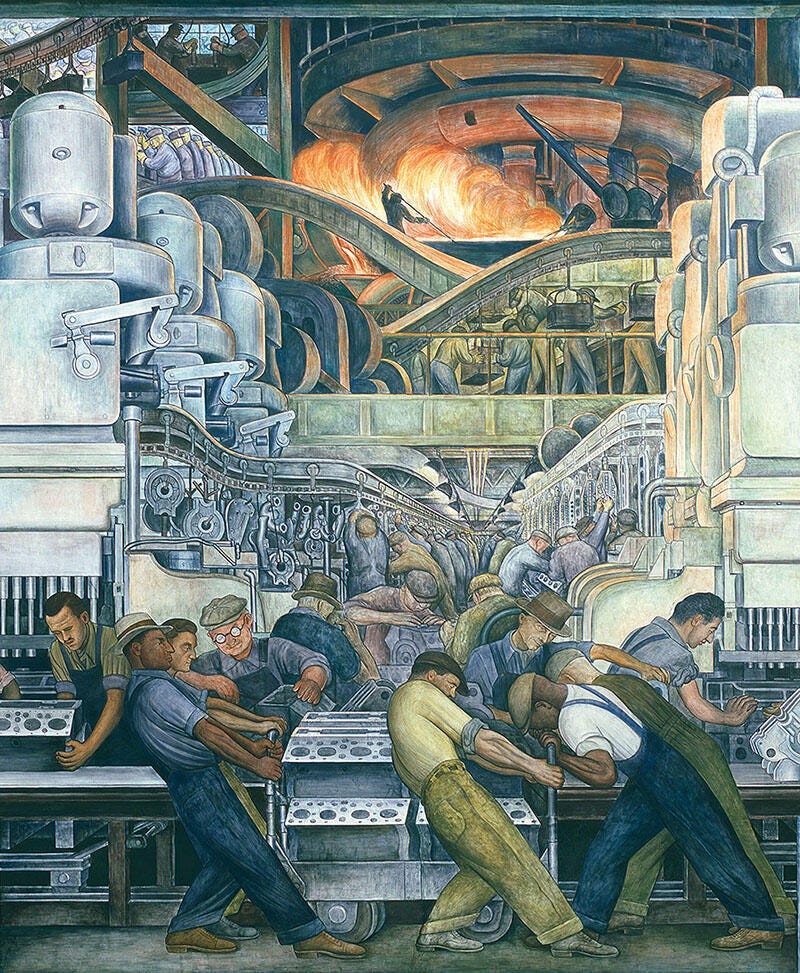

Dissatisfaction with the norm is an evident symptom of the current corporatist world that simply won’t budge. It breeds lethargy due to the performativity of the roles we hold in the workforce, as well as the meshing of market and social relationships. We spend our time appearing to be busy. We construct appearances and play characters of what we believe the role wants from us. This, of course, is work but not of the constructive or meaningful kind. It’s not what you turned in, it’s how you decorated it, and it’s not what you said, but the way you said it. Theatre has become the invisible skill most employers won’t admit they are looking for. My friend who works in a bank will regularly schedule Microsoft Teams meetings where he will be the only one in attendance just to sleep off his two-day bender from the weekend past. Productivity is his leading skill on his resume. As corporations have migrated towards the appearance of “a friend”, the boundaries between what is an acceptable working relationship have been slowly erased. The 9-5 is not relevant. We are now constantly contactable, expected to take extreme measures of commitment, and denied the expectations of wage increases, as the relationship is treated as if we strive and work together to achieve some greater purpose. Usually, shareholder profits. On both sides of this coin, whether you are feigning an interest to achieve a wage or are unable to get the man off your back because he thinks you owe him a favour, means that escapism looks more enticing by the minute. The working world paints a picture of satisfaction, care and attentiveness to a craft or pursuit. This is not tangible when what we develop is absent from the common good and is dictated by people who speak of community while patiently waiting for AI to finally get to a level of competency where it can replace us. When an essential relationship for many exists on a perpetually unequal footing, the repetitions of the weekly cycle will fall into place as expectedly as sunrise.

Tuesday’s the worst day of the week. Everyone knows this. I’m sitting on the U8 coasting by Schönleinstraße, Kotti, and Mauritzplatz. Purgatory, as I can’t seem to shake the repeated visits in this frame of mind. My comedown brain has decided they invented a shade of grey that only exists on this part of the train line that’s currently seeping off the platform through the windows and is climbing up onto my soul. I simultaneously can’t wait to get up to the cold air of the surface for some temporary relief, and wish to ride the U-Bahn as it circles the line for the whole day. They can make as many memes as they like on Berlin Club Memes, it isn’t going to shift the weight of consequences from weekly repeats of 72 hours of partying. Today, with all the fibre of my being, I will force the most minimum of efforts possible and will be physically present in the workplace. Please don’t talk to me. We will both regret the encounter. In retrospect, it’s absurd how many times you can revisit this situation. You don’t even have to be somewhere as exotic as Kotti. That particular shade of grey is present on all major public transport lines, having personally encountered it at Tottenham Hale, Jaurès, and Myrtle Broadway. A situation transcends all boundaries, creeds, colours and nationalities. Comedowns on public transport. Finally, something we can all rally around. Why am I doing this to myself? Well, through reasoning of a long and extended ripple effect. You see, one week I went out and enjoyed myself, and then I had a more difficult week than usual. Then I went out again, and because I had a more difficult week than usual previously, the weekend hit different. So then I dived back into the same cycle and week by week I’ve been ever increasing the extremities of each experience. Now I’m at a stage where if I don’t go out, the prospect of the weekend at home seems scary and empty. It’s also been several months, so I’ve forgotten how to talk to people outside the boundaries of work and under the impact of substances. It’s actually probably safer if I just stay in this routine.

The intent to stay in the churn, navigating the excitement, anticipation and spectacularly hard landings of the lifestyle, develops a bizarre ability to be 100% present and yet entirely absent from your experiences. The body becomes a shell with all lights on, given the expectations of it, while the mind ping-pongs between the present and the netherworld. A clear cause of these decisions, not so often acknowledged but evidently understood, is partying because we’re in pain. Momentary escapism hits different when what you have at home or in your head is not something that you wish to encounter. Pain seeks pleasure and disgust to hide its existence. The temporary appearance of another acts as a distraction, as fitting as an emotional manifestation of doom scrolling that satisfies the immediate.

The obvious criticism in this circumstance is the substances. Well, of course, we know we have the ability to exist in the space absent of substances (well done to all involved). Still, the reality doesn’t operate as efficiently as the stylised self-care tips listed on a Canva-created Instagram post. The illustration of self-care may appear inviting to the mind not in need of it, but to those caught in the cycle, words land empty and hollow. Littered amongst these guides and words of advice, you’ll meet the term “party break”. This phrase, while based on a sound principle, operates as efficiently as a band-aid on a leaking grain silo. It’s utilised to spend two weekends at home, and consider yourself cured. Delusion is a dish best served with mollycoddled platitudes and niceties for decoration. When partying for reasons of a broken heart, depression, frustration, or full commital escapism an individual seeks not to digress and decipher their reality (a process achieved over a significantly longer time than two weeks at home) but to place it in a box in their mind until it has the opportunity to leak out at the most inconvenient of times during the week. What’s learned over two weeks is simply inefficient in truly improving your situation. Party breaks always paint the opportunity for return. The essence of implied temporality is essential for anyone to recognise them. The reality of the situation often needs far more than “a break”. But of course, without the opportunity to return, why would anyone leave?

Don’t worry, you can always come back.

Don’t forget you’re here forever.

This experience is contained in a world that values appearances and social capital. While electronic music and techno as a whole is born of acceptance, anti-establishment, and outsider values, what exists now does not often swim in that lane. If you fall under the weight of your own consumption and excess, prepare to be quickly forgotten. Nobody enjoys sharing the load of a person who can’t hang. The lifestyle inadvertently and silently implies holding face under the immense pressure you invite upon yourself. Is it the scene’s or the individual’s fault? Well, it can be both. You clearly have a duty of care to yourself (tied your shoes, drank four litres of water and 3MMC free for a week? Well done, you! You’ve earned 3 days awake, have at it). However, self-care is a skill often performed and illustrated but not so often achieved. The knowledge seems absent in the community within the event, as to tread into this conversation pattern is to ruin the energy. Personal responsibility is not an attribute of abundance in a space of excess. You are unlikely to find true self-care in a toilet stall, and if you do, you probably won’t remember tomorrow. The wish to be included and the inherent need to escape normality will drive us continually back. That pressure to return layers into the psyche. You’ll find yourself perusing fruit in a supermarket when the song changes on your streaming platform and you wish to drop everything and go. All it takes is high hats and a kick drum to influx the lightness of being and a rush akin to childlike excitement. It’s sinisterly powerful, intoxicating, and I will admit, despite all experiences encountered, I still love it. We don’t have much to render this type of excitement these days. If it has to be this, then so be it.

Can the balance be achieved between this interest and a regular way of living? Yes, of course, it’s evident all around you. Age, career, and choices in what you want to do with your life can function harmoniously within electronic music and club spaces. The real question is, how do you do this? That, unfortunately, is something that’s done on more of a case by case basis. Annoying, isn’t it? Self-investigation is the beginning of the process. Why do we spend as much time on dancefloors as we possibly can? Each answer is individual, and the context of the situation is also paramount. If the value we place on the dancefloor is higher than the value we give to ourselves (you see this from your actions, not your immediate reaction), then the relationship is unbalanced. While this is fine temporarily (and is an extremely common experience), over the long term, this will unbalance your internal scales. While the physical detriments will increase with age, they will feel immeasurably worse when what’s needed internally is absent, lacking or unknown. What is the necessity? Well, I don’t know —you tell me; it’s your necessity, not mine. Where can it be found? Same place where all truth lies, internally.

It’s not unheard of to have this necessity revealed to you on the dancefloor. Great, but if it is understood there, then nurturing it will require care and attention off the dancefloor. Don’t get lost in the idea, break it down and act upon it. If you choose not to, then what’s been revealed is evidently useless. Proceed with caution on the above. This is not a mental health blog and never will be. Simply an acknowledgement of the destructive tendencies that exist in an outlet I care deeply about. Balance wasn’t something I was after myself. I didn’t want to alter my relationship. It became an inevitability. As it has gradually developed, the internal pining for escapism expands and retracts depending on what life has dealt me on that day. There has been an acceptance that it will never go away, and that’s ok. The self-acceptance outside needs to develop to be able to realise what’s beyond the doors and the queue.

Change in patterns of behaviour rarely alters who you are. They simply redirect your energy towards different patterns and experiences.

If your care and passion for the music and the experiences doesn’t end when you leave the dancefloor, then you have nothing to fear from changing or reflecting on what you choose to do with yourself.